Henry Hester Complete Interview

Henry Hester riding the smooth black hill at La Costa, California. Photo: Larry Balma

Henry Hester Interview

By Larry Balma

Back in the 1970s, big guy Henry Hester was a top pro slalom racer for G&S and skate car driver who, oddly enough, founded the first-ever pool contest series, the Hester Series, in 1978. After spending the 1980s and ’90s working in the snowboard industry, Henry earns a living today driving a taxi cab in Encinitas and still occasionally races slalom.—GSD

Where did you grow up?

I was born a rich kid in La Jolla. My dad was an architect. I had a really nice upbringing. I went to La Jolla Elementary, all the way through La Jolla High School. Windansea beach was three blocks away, so there was surfing really close by. I started surfing really early, in 1959, when I was eight or nine years old. My first surfboard was made out of balsa wood with a white tip on it. I got a really good start from my dad, who would take me surfing with his buddies. So, on the weekends, we’d go down and surf all of the beach breaks at Pacific Beach and La Jolla Shores. I was riding a 9’ 1” balsa wood Hobie. It was a cool board back then and is probably worth $50,000 today. Then we moved on to foam surfboards with a one-inch stringer. I got a Hansen’s surfboard matching my dad’s. Mine was a 9’ 1” and dad’s was a 9’ 10”. We got those at the Hansen’s shop up in Cardiff.

Henry living life driving his taxi. Photo: Lance Smith

I put my surfboard on my head and carried it down to La Jolla Shores, and all of the older local guys down there who were already in Windansea Surf Club were ribbing me. I had a sticker on the bottom right in front of the fin and another one on the top, and they said, “Hey, dude, your sticker is on the wrong side of the board!” I was a pretty strong surfer all the way through junior high and high school. I was fortunate having graduated in 1970, right during the cutting edge of the short board revolution. So, I was right there, following George Grenough, Bob McTavish and all of those guys in Australia, where all of this was happening. I went to Carl Ekstrom, who was making our longboards at the time and asked him to make me a V bottom. We didn’t know whether to put a fin on it or not. You know, we had a big old giant V bottom tail, and we had not seen any V bottoms at all. We had only seen them in the magazine. The only guy who had one in California was Steve Biggler up in Los Angeles; he brought it back from Australia. But, I was the first guy to get a V bottom surfboard from Carl Ekstrom. It was an 8’ 10”, which was something I couldn’t ride at first. No one could figure out how those things would tip from side to side.

LMB: Who made that board?

Carl Ekstrom shaped it, and we didn’t know whether to put a fin on it or not, because all we could see was blurry pictures coming out of Australia. We got the pig shape pretty much nailed down with really thin rails in the back. It was a nice board. But, we didn’t know whether to put a fin on the bottom of that board, as the V might have worked as a fin. That’s how primal this thing was. So, anyway, we finally went to Windansea, dropped in and banked off the bottom. From then on, I was able to transition between a regular bottom board to a V bottom. It was a giant transition to make for guys at that time because the V would tip and throw guys off. Anyway, that was the early years of high school, and then we went into short boards. I had a local guy George Taylor shape me a lot of boards. We would go down to Mitch’s Surf Shop in La Jolla and buy all of the materials for $28 to make a board. We’d get a seconds blank with a hole in it, and a bunch of resin, fiberglass, surfacing agent and all of that stuff. We’d start the board Friday afternoon and I’d be riding it Sunday morning, sometimes before we even hot coated it. We’d go through a board every week, so there was a really fast transition there. I got into competitive surfing after my skateboarding career. When I was about 28-30 years old, I started surfing pro contests in California.

But, a lot of the flow of the design of skateboards came from surfing. It came from our ability to be able to pump the board, gyrate, and flex the board. We used a little bit of ski flex on those flexible boards we were riding at the time. That came from surfing. I rode a fish surfboard back in the day. I must have had 30-40 true keel fin fish surfboards. The other guys were riding twin fins, which were a little bit different. Fish fins are straight, keel fins are canted in, and I stuck with the fish design way longer than other guys did. They had progressed onto other kinds of boards, and I stuck with fish boards for 20 years. It’s really interesting to drive up and down Encinitas, or anywhere in California, and see all of these guys with their fish boards, with their acid color designs on them like the ’70s. God, I was right there with that. I was one of the first guys on that, so I feel really good about it. It actually makes me feel kind of cool. Not really.

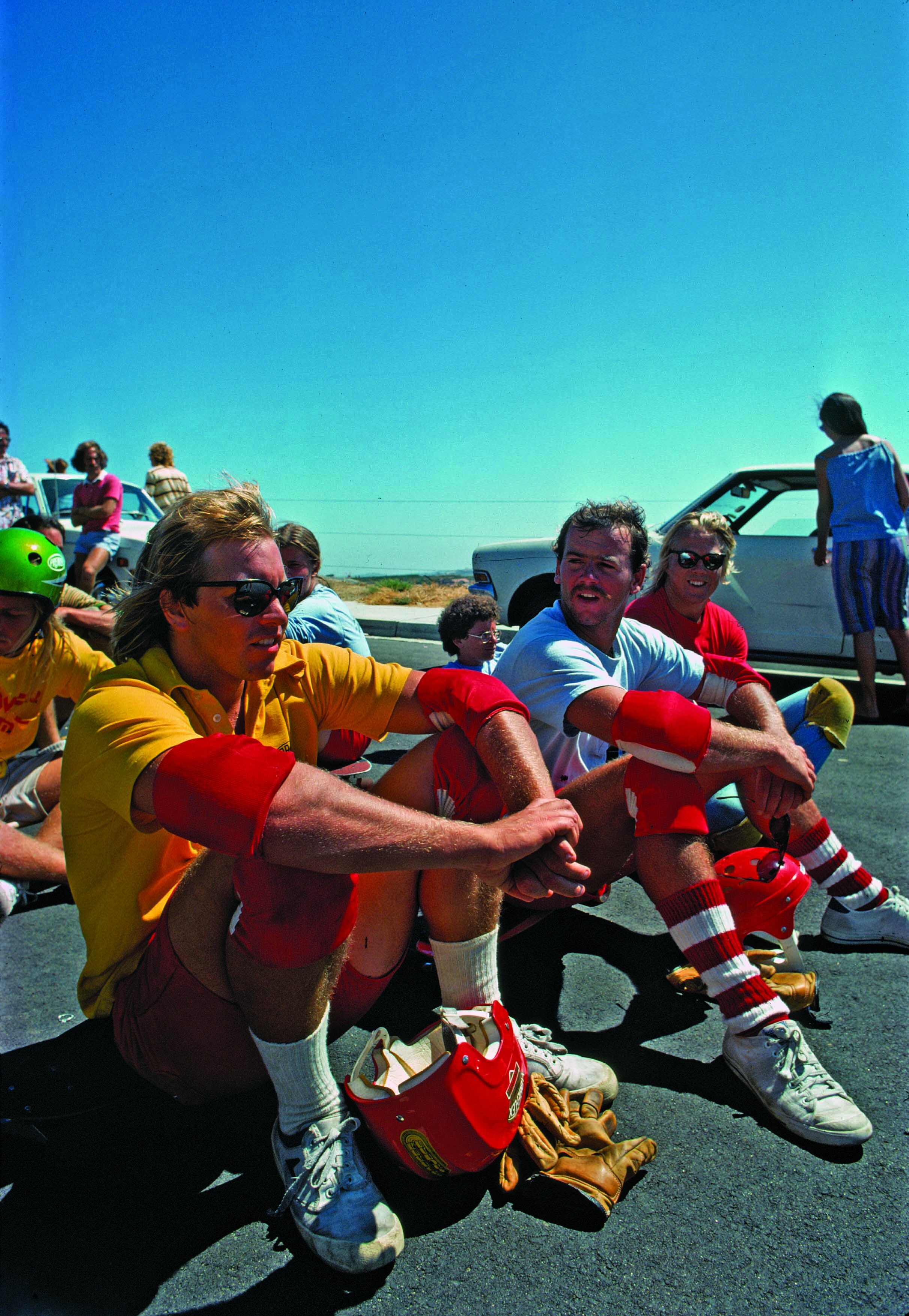

Taking a break at La Costa. Photo: Jim Goodrich

LMB: So, how did you hook up with G&S?

Well, G&S came about through my surf connections: Gary Keating and Bill Andrews, the guys who were working at Pacific Beach Surf Shop. But, before that, what really happened to get me back into skating was a call on the phone from my friend Bob Skoldberg. He tells me that I got him into it, but, actually, it was him who got me into it. I was just coming back from doing a year in Sun Valley in the Watergate year, 1974. Bob called me up and said, “Hey, we’re skating up in La Costa. This place is unreal! You’ve got to get one of these boards and come on up.” I was into it. I thought it would be cool. So, I borrowed a board and went up on a Sunday. The first boards we rode were those little orange Bahnes with Chicago trucks and little clay wheels. We were riding on some pretty crude stuff. Those were the days of the cones with the square bottoms. You’d hit ’em and go flying.

I’d seen slalom racing up in Sun Valley, and I was really into that. I had seen guys experimenting riding with their feet parallel on one water ski up in the snow at Sun Valley. Snowboarding hadn’t started yet, at least that I know of. That kind of transitioned to my love for skateboarding, which came through Bob Skoldberg, and through this guy Steve Eally. Steve dropped out after a couple of months, but Bob and I continued to make friends with all of these new guys we’d never met before. We made bonding friendships with Bobby Piercy, Tommy Ryan, Mike Williams, the photographer and skater Lance Smith, Di Dootson and all of these people who were up in La Costa. I started skating the weekly races, and we’d all throw in three to five dollars. Bob and I would do well and take home 35 bucks. We thought we were pro skateboarders at the time. It was classic. We had a lot of fun. When I look back on my skateboard career, that was a really good time to remember. Anyway, that led to other things. I can go into the Hester Series and all of that. I did a lot of different things in skateboarding. I did the downhill skate car thing. I could never stand up going down hill past 35 mph. I have very weak ankles and I’d get the shakes. I don’t care what truck set-up I had, I’d get the shakes and wobbles, so I wasn’t able to do that. I weighed 205 pounds, but I could ride in the skate car and do well in that. I feel like it was a personal mistake not to have started a company like my friend Tom Sims. I probably could have started Hester Skateboards or some sort of company and done pretty well with it. I have a good business sense, but I just never really felt confident that I could do that, which was a giant mistake in my life.

The message to anyone who reads this would be that if the doors open, go through them because if you don’t, you’ll regret it for the rest of your life. Tom Sims went through the door, Stacy Peralta went through the door, Tony Alva went through the door. Other people took a chance at owning a business, but, at the time, I thought I just wasn’t savvy enough. Now I realize I could have done that. What I did was give back to the sport. I did the Hester Series skateboard contests. We ran four contests for the pool riders, who previously had no contests. They had no chance to be competitive. Back in those days, competition was a big thing. And pool riders would have to do flatland skating and go up against trick guys. I’m talking about the Dogtown and Upland guys. Warren Bolster didn’t know them. So, I started a series of pool contests, and, all of a sudden, all of these no-name guys came to light: Steve Alba, Micke Alba, Steve Olson, Scott Dunlap. All of these guys came out of nowhere and, in one year, became skateboard stars, and rightfully so, because they ripped. We just didn’t know it.

Needless to say, Warren had to get a bigger phone book to handle the load, because there were a lot of new stars, and I felt proud that I was able to introduce a lot of these guys to the industry. It was almost like the start of the X Games, but at a lower level. We ran four contests one year. I got all of my slalom buddies, Mike Williams, Bob Skoldberg, and the late Curtis Hesselgrave was the head judge. We worked with Tony Alva on the scoring system, and how long the guys would want to be in the pool. We started off judging every single trick from 1 to 100. Each judge had a girl tabulator next to him, and he’d shout out 75, 83, 45, 100, 14, you know. It was just crazy. The guys who did the most tricks pretty much won. I got a call the next day from Tony Alva, and we worked out a better system: 45 seconds in the pool, 1 to 100, judge just what the guy did, and it turned out to be much better. That format continues as the judging system to this day, and it all came from Tony.

Henry Hester and Bob Skoldberg’s taking a break at La Costa. Photo: Jim Goodrich

LMB: So, you didn’t start your own company, but you had a pro model with G&S.

Yeah, I had a pro slalom model with G&S. I had my signature right there on the Fibreflex logo. It was a cut-away model, because, back then, we rode with our feet parallel so we could turn the board faster.

LMB: You really used the flex. They made those boards for different weight people so that you could really spring like a ski.

Yeah, we would have it laminated with different levels of wood, some stiffer than others. Actually, the stock boards were really flexible. I couldn’t ride the stock board. I had to ride one that was a little beefier. I was doing this at 25-26 years old; so I was big, I was a grown man. They were making boards for kids who weighed a buck twenty-five. They couldn’t flex the boards I rode, they couldn’t even turn them. But when they got on the stock boards, they could flex them and turn them. They were really springy. It’s interesting to fast forward to 2006-’08, as flex boards don’t exist anymore in slalom. They’re all stiff—the flex comes from the truck system. The front truck moves and the back truck follows the front truck. The whole pattern of skating has changed. There is no room or no time for flex anymore, the riders go too fast to have the board flex, flex, flex.

I went to a contest in Austin, Texas when I lived out there for a year-and-a-half. I had a flex board, and these guys were all laughing at me. They had stiff wood boards: Pavells, Skate Kings, and all of that stuff with kicktails on them and the trucks mounted back. So, the back truck wouldn’t turn and just followed the front truck. I wondered, “What’s going on here?” I made the mistake of switching boards during a contest. So, there I was at 59 years old, trying to skate, and I did all right after I got loosened up with a little bit of aspirin. So, I got a hold of Roe and had them send back some of my old boards, and asked some of the guys I sold boards to on eBay to send them back so I could ride. I came with three flex boards, which was completely the wrong idea. I went into the contest with old school technology, and the guys got me on something more modern quickly.

Richy Carrasco, the king of knowing what to put a guy on, got me all set up on a concave kicktail. It looked like a regular pool board that was shaped narrower. It had what are called money bumps, so it wouldn’t break in half, which they used as a toe accelerator pedal. So, all of the bumps and twists and curves you see on these modern slalom boards, plus the kicktail lift in the front, and the nose block to keep your foot from falling off the front of the board, all have a purpose, and it’s all very technical. The trucks are all machined and cost $350 per set. But, it all came from Tracker, Chicago, and Bennett.

Henry engages the cones at La Costa. Photo: Warren Bolster

LMB: Where did you get your first set of Trackers?

I think my first set of Trackers came from Dave Dominy. He was racing with us. He was a fidgety guy working on all of the mechanics of the trucks. There were a couple of guys who had them; we weren’t the first guys to get them. What we were riding was Bennett. They didn’t have Bennett Pros yet, which were a little bit wider. We were riding the Bennett trucks, which led to the Indy geometry. They were quick turning. When the Trackers came out, they had the set back geometry, which was a little bit slower turning. So, Trackers were more stable at higher speeds, and were thus better for the pool guys, because they weren’t quite as fidgety and nervous. So, we were riding Bennetts with these really wide wheels; we were getting the length, and the width, but we were trying to push around all of this urethane, and it just didn’t work. When the Trackers came out, we were able to use smaller wheels, and that was really good, because we had the width and we had more distance between the wheels, and, in slalom, the distance between the wheels was almost more critical than the distance on the outside.

Another thing we did was make a narrower wheel because we didn’t need quite so much urethane. It was so soft and grippy at the time; we didn’t need big, wide wheels. The wide wheel thing lasted for about three months until Tracker Trucks came along, then it was okay to switch from the wide wheels back to the normal Road Rider 4 and get some separation between them. The thing that threw us off a little bit at first about Tracker Trucks was they were so wide that the wheels stuck out, and we weren’t used to that. Looking down on the board, you would be afraid that your toes would hit the wheel and stop you. At the time, we were riding sideways on the board, so we had to learn to move our feet back a little bit and adjust for the wider trucks.

Hester, Lance Smith, and Hal Jepsen at La Costa. Photo: Larry Balma

You know, it was like night and day riding down the hills. It was unbelievable! Our speeds went up, like, two seconds, which was a 20% increase on a 10-second course. Changing to Tracker Trucks increased our speed by 20%. That’s how revolutionary the trucks were at the time for slalom. What was cool about it is that the pool riders could ride the same trucks and get the same benefits. They could have more aluminum on the coping and were able to grind better, so it worked out for everybody. At least I think it worked out for Tracker, as I’m not sure if they ever made it or not.

We really enjoyed Tracker Trucks, because they really worked great. We rode them all over the world. At first, the Tracker Fultracks were something you had to adjust to as far as your skating style because the wheels stuck out on those narrow boards we rode. You had to adjust your stance a bit. But, I’ll tell you, the width and the stability in slalom was really important. We went with a really sharp wheel on the inside. We didn’t use the conical wheels because they would drift. We needed an edge there to know where we were on the ground. If you used a conical wheel, it would tend to slide and drift, so you wouldn’t get that edgy kind of turn. So, that’s why all of the slalom wheels have always been square-edged. Those rounded wheels on the Sector 9 boards should have curved wheels.

LMB: Do you have a favorite Tracker ad?

Henry Hester in a Tracker ad, August 1976

I was in one ad that was made into a big poster. I’m not going to say that was my favorite one because I was in it, but because it was a good slalom picture. I think Warren Bolster shot it. I believe Road Rider, Tracker, and G&S went in on that ad.

LMB: Well, Tracker used it for an ad, and then G&S and Road Rider went in on it with Tracker for a poster.

That was all the business side of it. I was a skater who was just into bearings, grommets, cushions, nuts and bolts, and going down the hill. One thing that was different between myself and a lot of other guys was that I wasn’t into drugs or drinking. I was a straight-edge kind of guy. When it came to these contests, they would be partying, and I’d be in the hotel room just nerding out, squirting WD-40 into my wheel bearings to make them go faster. I was a really nerdy guy in slalom. You have to be a tech kind of guy to be a slalom racer.

LMB: It seems like you slalom guys had some mental strategy in your competitiveness.

The mental thing was the most fun part, because slalom skating is so objective, because of the time. You got an 8.3, he got an 8.8, and you win. Pretty basic, right? So, that allowed us to give each other crap, and to really work on each other mentally. You couldn’t do that in pool riding, or mega ramp riding, “Hey, dude, you suck!” But, you could do it in slalom, because if they sucked, they sucked. The fun part between Bobby Piercy and Tommy Ryan was that they all loved the banter back and forth. The last time I raced Ryan was in 2003, two old men racing down this course on national Fox TV. I was talking to Ryan the whole way down, “Hey, man, this is great! We’re having so much fun! You suck!” and Ryan said, “Shut up, Henry. We’re on TV.” The back and forth bantering had a lot to do with the betting. We’d throw down our money and bet that we were faster, but it didn’t cost much, and it was really fun. Bob Skoldberg and I would split our money 75/25. Over the course of three years, we traded $3500.

Those were the days when the rules were being written. We would help out with the rules for the International Skateboarding Association. I’d drive up to LA and work on the rulebooks—type out and try and figure out the rules, like, what if there was a tie? We literally wrote the book on slalom. Myself, Sally Ann Miller, Di Dootson, and a lot of us spent time writing down the rules that are still used today. That was a viable thing that we did. My career was in building and running contests: the Hester Series, and the La Costa Open for a couple of years. So, I’ve done my share for the industry in running events. I’ve also done some announcing, and it’s always fun.

One of the many Hester Series bowls this one at Upland, California. Photo: Lance Smith

Henry’s smooth style. Photo: Waren Bolster

LMB: What was it like working with Curtis Hesselgrave?

Curtis was the first skateboarding trainer who we ever knew, and he would help us at La Costa. He would put a beach towel down on the asphalt and help us stretch. If someone had a problem, he would massage it and get it squared away. But, it wasn’t just that, he was a fin developer. He went on to make the fastest windsurfing fins, built countless surfboard fins, worked at the Bing factory, and helped them on the foils. We lost Curtis just this last year. He was the head judge of the Hester Series. He was in charge of the skaters, the banners, and keeping things going, like Dennis Martinez knocking himself out at every event, going to the hospital, etc. Curtis stepped in as head judge because we didn’t want the judging to be subjective or unfair. It was really hard to be fair in judging, plus a lot of tricks happened in the Hester Series for the first time, like the first air, the first rock and roll. We saw history when tricks were done the first time: they knew it, the crowd knew it, and the judges stood up and applauded. But, it was hard, because that was just one maneuver, and the judges still had to judge the whole run. That was where Curtis came in. He was able to settle down everyone and look at the entire run. Was that better than Steve Olson? No, but it bumped him up a bit. That was what Curtis could do. Subjective judging is very difficult. I had Mike Williams, Bob Skoldberg, I think Ray Allen might have judged. These guys were all thinkers and were able to articulate that what they were seeing in the Hester Series was all-new. Every single trick they were doing was new and didn’t have a name.

And it went on with the Gold Cup series with Neil Blender doing the Wooly Mammoth and all of this weird stuff that he would name. They were naming tricks by the week. Nowadays, every trick has a name. All of the tricks now are combinations of three or more tricks. And Blender named a lot of tricks in his day in the ’80s. He invented them and then had to name them. But, getting back to Curtis, he was able to keep a lid on it. One of the things that we prided ourselves on was that when we ran contests, we didn’t listen to the manufacturers. We didn’t listen to Jay Shuirman, or you guys at Tracker or G&S. Knowing that a skater was putting it on, the companies stayed out of it, because of the politics, and it was really cool in that regard. And I think it stayed that way—it’s not hard to tell which guy is ripping.

LMB: The manufacturers were much happier having the skaters in charge of an event than a promoter.

Now you’re talking my world here. That’s what I contributed to the industry—the skater competition thing. There were a lot of contests like the FreeFormer one, in which the rules would change halfway through. Bob and I would drive home from an LA contest and just be so mad because the rules changed. A couple of funny things happened at these contests that were memorable. One was this Long Beach contest that involved a Logan / Tracker skater, Torger Johnson. This contest dragged on into the middle of the night. They just couldn’t organize the thing. We were having a slalom contest on this big wood ramp. It was about 30 feet high with eight slalom cones and a little runout. I think I won that event against Tom Sims.

Then they had the downhill event, in which you went through a timing trap with two rows of lights. So, there was a light beam about a foot high, and I was sitting there figuring how to cheat it and win. Torger Johnson was up in the bleachers waiting for another event. So, I said, “Torger, do you want to win some money in downhill?” Torger replied, “Well, I’m not really a downhill guy.” I said, “You won’t beat me, because I’m better at it than you, but you’ll win some money. It’s $1,000 bucks for first place.”

LMB: Was this at the Free Former contest?

Yeah. So, I told him there’s a beam here and there’s another beam ten feet away. What they’re measuring is how quickly the beams get broken. So, what you want to do is come down as fast as you can, but you don’t have to go that fast. Just pull your leg back on the first beam and then quickly reach for the second beam. That’s how I did 28 mph instead of 26 mph, and I got $1,000. Torger did 27 mph, and he went home with $350. I always figured he owned me 10% of it. Skoldberg was always pissed at me for not telling him about that trick. It was just because I was stoked sitting next to Torger, and he was a cool guy.

Another tidbit: there was a race between Tony Alva and myself at Carlsbad skatepark on an asphalt ramp. Search “Hester vs. Alva” on YouTube. There are two races that they combined into one. What happened was we had taken run after run, and the timing lights weren’t right. I won one, Alva won one, and I won another. Finally, I think it was the fourth run, and we were getting tired. It was the finals for first place, and Alva was already winning the whole entire thing. He was just trying to win the slalom. Thirty million people were watching it on Wide World of Sports on national TV. We didn’t know that many people were watching. It was crazy. It went on to be a very famous race because I crashed. I had a great second run, pushing mongo. I got a jump on Alva and beat him by eight feet, a comeback by a tenth of a second. But, to this day, I felt that the timing lights were screwed up. I’m a mongo skater, which means you push with your front foot.

The word mongo came about after the Ollie era in the mid-1980s. Mongo skating is not the way to skate, kids. Always push with your back foot, not your front foot. Some skate historian should know where the word mongo came from. Maybe Ed Economy would know. Mongo was big in La Costa. Tommy Ryan, John Hughes, Bobby Piercy, and Chris Yandall could skate either way. I can’t do a foot brake mongo. I left four or five contests because I couldn’t use a foot brake. I got involved in the snowboard industry in the early ’80s with G&S snowboards, went on to be the sales manager at Lib Tec and Gnu for about three years up in Seattle, then I started Rusty Snowboards. We built our own boards at Rusty, really nice boards, I was more into the snowboard industry than I was in any other, to be quite honest. But I’ve worked for Gordon and Smith, Santa Cruz, Rusty, Lib Tec, Gnu, and San Diego Trucks. I’ve had a lot of great jobs in the industry, and when I look back on it, I should have started my own skateboard company.

Bob Skoldberg: Henry built the Rusty snowboard factory from scratch.

I learned a little bit from Gnu and Lib Tec, but I used all different hard tooling technology. When we had to clean it up and sell it because the Japanese yen went out, we had to shut down our factory. We were making three to five thousand boards per year. Half of our sales went to Japan and they cooked us. I cleaned up and sold the factory stuff to one guy who moved it out to New Jersey. I had the most unbelievable presses, and I sat there and swept up the factory. It was as clean as a whistle, and I sat there and wept like a baby, and just cried. It was an emotional drain. I put my life into this Rusty thing, and I drove home. It was tough. We’ve all been through the same thing, thinking, “I’ll never make it again.”

Friends for life: Bob Skoldberg, Di Dootson, and Henry Hester. Photo: Jim Goodrich