Jim Gray's Complete Interview

Malibu circa 2012

Jim Gray Interview

By Larry Balma

A product of the late 1970s So Cal skatepark scene, Jim Gray proffered a clean-cut image during punk rock’s heyday in skateboarding in the ’80s. Not only was Jim the originator of two tricks that bear his name—the Jim Jam and the Gray Slide—but he also skated pro for G&S then Blockhead, went on to found his own brand, Acme Skateboards, followed by a woodshop called ABC Board Supply. Today, Jim runs a sticker company called Inkgenda and still powers around the tranny like the tried and true barnstormer he is.

—GSD

So, Jim, where did you grow up? Well, maybe you haven’t grown up yet.

I’ll quote my dad: “I didn’t grow up, I was thrown up.” I was born in Los Angeles in Monterey Park. I lived there until I was about six, then I moved to Westminster/Fountain Valley in Orange County. I grew up in OC when it was half lima bean fields and strawberries, and half tract homes.

When did you start skating?

When I was eight or nine, I got a little plastic Grentec board at the local drugstore. That was when I first rode a skateboard. I had a Black Knight before that, but it was just a skateboard to roll around on. I really started skateboarding somewhere between seventh and eighth grade. My brother was a lot more into it than I was. On a Saturday morning, he would ride his moped from Westminster to Mt. Baldy, which was a two-and-a-half-hour drive on the back roads—no freeways. Eventually, he and his friend, who had a Honda 90, would pull me onto the back of it and start taking me with them to Skatopia and places like that. After I only skated for a few months, I got sponsored at Skatopia. I always felt bad about that, because my brother was such a diehard. That was the beginning of the skatepark era.

1988 Tracker Trucks ad with Marty Jimenez and Jim Gray.

When did you get your first set of Trackers?

When I was riding Big O skatepark, Trackers were on some of the boards. I never bought a skateboard, other than the Grentec and Black Knight. I won a complete skateboard at a shop called Sunshine Skateboards in Fountain Valley. When I was done with that board, I took the trucks off of it. I don’t remember what they were. I bought some wheels at the Vans store, and I made my own boards out of ash. Then we started making boards out of plywood and putting resin and sand on them for grip. After that, I got sponsored, so I never really went in and bought a pro skateboard deck anywhere. I made a bunch of them, but I never bought one.

One of my first sponsors was Pro-Am. They made a complete Tracker knock-off. Then I was riding for Powerflex when Lance Smith asked me to ride for Tracker. The ironic thing is Duane Peters asked me to ride for Indy at the same time because we both rode Big O skatepark. I didn’t give a shit about image or whatever anyone was saying, so I said, “Give me a set and I’ll try them.” I tried both trucks, and Trackers just worked better for me. My decision to ride for Tracker was based purely on riding them and liking them better than Indys, which were too squirrely for me. I didn’t own a set of Trackers before I got sponsored by Tracker.

Why is Tracker so important to the history of skateboarding?

Tracker was the first true quality skateboard truck. Tracker stepped out of the roller skate era with a truck designed for skateboarding. It all looked professionally done. It wasn’t a shitty baseplate with a decent hanger like Bennett. At the time, the design caught my eye. I liked the simplicity of the smooth hanger. Bennett had a squared-off hanger. Tracker took it to a different design aesthetic. I liked the way they looked. All of the riders who rode them impressed me to no end. Tracker had an amazing team.

Do you recall any memorable times with the Tracker team?

Most of my memories are from when I considered myself an older, washed-up guy. I was working with you at TransWorld and riding for Blockhead. I wasn’t Tony Hawk, you know what I mean? I wasn’t the guy they called for, saying, “We need Jim Gray here for a demo.” I got that, I always knew that. I was lucky enough as it was to get to go to the contests and ride with those guys. Someone had to get 30th place so someone else could win.

Jim putting his magnesium Tracker Sixtracks through the paces. Photo: Grant Brittain, circa 1988.

You were usually in the top 15.

I was there, I knew I belonged there, and I earned my way there, but part of it was I had all of those other interests. I wanted to go work on the wheels, I wanted my real estate license, I wanted those things. Most of the guys I grew up with were happy skating eight hours a day. I loved skateboarding, but I loved doing something else, too. I tried a trick once or twice, and if I didn’t make it, I just moved on. Those other guys would work at it, but I didn’t have the patience for that. I’m too ADD. I always wanted to do too many things. I was never part of the clique of skateboarding.

Now we’re going to ask a few questions from GSD. Why do you huff and puff so much when you skate?

I never knew that I huff and puff a lot when I skate, but I talk to myself when I skate. I always heckle myself, because I hear myself say stuff like, “Damn it, that sucked! You’re such a loser!” I make fun of myself when I skate when I know I can do something better. So, although I’ve been accused of talking to myself when I skate, I don’t know if anyone has ever accused me of huffing and puffing. I’m sure talking to myself doesn’t surprise you at all, because I talk to anything and everything nearby. I sit in this office by myself and there’s usually nobody here, so I talk to the wall. I used to have telephone conversations with you [Larry] and I wished I could reach through the phone and strangle you, because I’m so hyper and you’re so calm, and I’d sit and wait for a response while you sat there thinking. I wanted to slap you and say, “Just spit it out!” GSD is awesome. He’s played a vital part in skateboarding at Tracker and TransWorld. He’s different, but it’s a cool different. He found himself, and that’s what he should be. I knew his question would be weird.

What’s a Jim Jam? How and when did you invent it?

Some people call it a backslide sweeper, but I did the Jim Jam before the sweeper was even invented. So, a frontside sweeper is really a frontside Jim Jam. Duane Peters and I could argue about that one forever. During a sweeper, you set your tail down, but I never set my tail down in the Jim Jam, which is a continuously moving trick. You basically roll your wheels on the deck, pull on your nose and jump back on your board as you go in. Don’t touch your tail on the deck or coping. That’s the technical difference between a Jim Jam and a sweeper.

I did it on accident in the Big O clover bowl when I was probably 14, which was in 1977. I’d do tail taps and sometimes my back foot would slip off. I didn’t want to jump off of my skateboard, so I tried to put my foot back on. But, it’s easier to put your foot back on when you’re going in than when it’s on the coping. So, I’d stand there holding my board, then pivot and jump back on it. Somehow, after doing that a bunch of times, I got the confidence to just fling myself back on it. Eventually, I would drag it way behind me, pull my nose and just fly back in. It always seemed like a very easy trick, very no-brainer. I never felt scared doing it. I don’t think I’ve ever hung up and slammed doing a Jim Jam. It really cracks me up how many people are scared to death of trying it. I guess I should be honored, but at the same time, it sucks, because there are only a couple of young kids—Grayson Fletcher and Robby Ruso—who do it now. But, I’m stoked it’s staying alive. It was almost dead. I don’t think anyone did it for 20 years. That’s what’s so awesome about skateboarding: there are other people who do tricks that I would never try because it’s too dangerous. I do the Jim Jam and it’s so easy, like a warm-up trick, but other people think it’s deadly.

Jim with his lovely wife Michelle at the Action Sports Retailer Trade Show circa 1980.

Who named it?

The only two tricks I’ve invented—the Gray slide and the Jim Jam—were both named by Neil Blender. You can picture Neil after I did it, just blurting out, “It’s a Jim Jam.” That’s how things come up with Neil.

That’s GSD’s next question. What’s a Gray slide? How and when did you invent it?

Before the Gray slide, laybacks were done on the vertical wall, but I’d grab my nose as I grinded, put my back hand down, snap onto my tail and spread out like a layback on the coping—all continuously moving—then drop back in. So, it’s really a high-speed grind to layback on the coping. If you do it properly, your tail will slide for a block or two across the coping. You come in half sideways and straighten out on the way down the wall. I don’t know when I invented it, maybe 1978-’79 at the Big O while I goofed off in the little bowls. It probably happened on accident—I have no idea how.

Did you invent both of those tricks on Trackers?

Yes, for sure. I was on G&S and started riding Trackers when I was on Powerflex, so by the time I was on G&S, that’s all I was riding.

Did you get trucks from Tracker or G&S?

I’m pretty sure I got trucks from Tracker because I had met Lance Smith. I remember coming down to Tracker when you were by the power plant, off of Palomar Airport Road, and going into the shop. That’s the first time I remember going to Tracker.

That was probably in 1980.

G&S would give me wheels, bearings, mounting hardware, and grip tape. They gave me everything I needed, so I honestly don’t know what year I officially started riding for the Tracker team.

In the beginning, our team would give a box of trucks to Logan, and a box to G&S, and they flowed them out. They would give them to you riders, and you’d go on demos and trips and flow a set of trucks to somebody.

It’s kind of funny that the G&S team rode for Nike. They said they wanted to sponsor our whole team, so every two months, they would ship Steve Cathey a big box of shoes. In fact, the first skateboard ad I was ever in was ran either in Thrasher or Action Now, or maybe both. It was a G&S and Nike split ad. I think my first ad said, “Nike pro team rider Jim Gray.” But, I didn’t talk to or know anyone from Nike. A lot of that stuff is definitely different today.

Do you remember the Brainstorm Design days?

Of course I do. My perspective of how that started is I worked in the mortgage banking business and made decent money. I honestly thought the skateboarding business was pretty rinky-dink. I thought I was going to be a real estate mogul. I got my real estate license when I was 18, but I got bored with the people in that industry, then I ruptured my spleen skateboarding. When I was off healing, I just didn’t want to put on a suit and tie, and go back into that friggin’ office and underwrite loans. So, I did independent real estate appraisals. I remember coming down and talking to you [Larry]. My spiel was, “Hey, I would love to help you do some stuff, but I’m not going to be some kid you give 10 bucks an hour to work in the warehouse. That’s not who I am. I want a piece of something.” I could see, just from knowing you as a sponsor, that you had so much stuff going on. You owned Tracker, you owned TransWorld, and you needed people who could help you do things. But, I didn’t want to be just another employee, so I threw that out there. You responded, “We’ll set up this separate company,” and I had no idea what we were doing, but I said, “Okay, let’s do it.” That’s how Brainstorm started.

You didn’t think about me working for TransWorld. Okay, we started Brainstorm, and I know we worked on a couple of projects for Tracker, then it was like, “What else can I help you with?” My idea was to be of value and make things happen. And you said, “We could use some help with TransWorld ad sales,” and I said, “Okay, I can sell ads, too.” A good way of describing it is, it was a pretty organic. We found a way to finish what needed to get done. I enjoyed the projects I got to help out on; getting the wheel project going, and even putting the tiny washers on the trucks instead of the big, old-fashioned ones. Making little changes like that made me really proud. Brainstorm was fun, but the Tracker watch deal didn’t work out. I learned something new every day. Like, “How many should we buy?” You said, “Let’s make a 1,000 of them.” I still remember the first phone call you made to a distributor, who said, “I’ll take all of them.” “What the hell? Shit! We need more of these things!” Those were different times.

The first Tracker watches were good.

They were really good, but the broker for the watch factory in Hong Kong changed them from Swiss jewel movements that run forever to Hong Kong movements that wear out fast. The batteries wore out quickly, too. I think about that to this day. I tell people stories when they talk about manufacturing in China. I learned my first lesson in 1986. We ordered 1,000 Tracker watches, and in my first sales phone call, they were gone. So, you ordered 10,000 more. Then Brad Dorfman got wind of it and said, “I want some watches.” So, another 10,000 watches were coming and were probably all sold, too, so Tracker stepped up for another 20,000 watches. Then Brad ordered another 33,000 watches. So, I had one order for 53,000 watches coming and that’s when all of the movements were changed. To this day, I tell people that crooked brokers probably made 25 cents more off of each of those 53,000 watches by putting the cheaper movement in there. He ended up getting himself in a lawsuit, which screwed us all up and killed the Brainstorm business we started. He had to write us a check for somewhere around $100,000 to $150,000. The whole thing was a mess, all so the guy could make an extra $10,000 by changing a part.

That really soured me for working offshore.

Later, when I started making things for Acme, I’d order 1,000 backpacks with metal zippers, but when they arrived, they had plastic zippers. I was like, “What the fuck?” But, back to the ’80s, I specifically remember our first run of the Ollie Wheels and Lester Marbles was 80,000 wheels. We did 20,000 of each size of the Ollies, and 20,000 of the Lester Marbles for a total of 80,000 wheels. Anybody starting today does not make 80,000 wheels. If they make 4,000 for their first run of wheels, they’re going big. This was a new thing. Tracker was established, had a reputation, and was able to sell 80,000 wheels. But, while we were waiting for Tom Peterson’s urethane machines at his new company Hyper Wheels to get built, G&S had some emergency, and right when the machines got done, G&S got the first run out of Hyper Wheels, because they came in and said, “We need 250,000 wheels! Then we were like, “Jesus Christ!” So, I was learning every day, watching stuff that was going on around me. I realized, “Okay, maybe there is some volume in skateboarding.” It was all fun, it taught me a lot. We used to have our board meetings, which taught me a lot about organizations, financial planning, and the structure of stuff. It was good times, with lots of good lunches with Steve Angus and Mike Staffari. Brainstorm Designs was a good part of life. It probably would have gone a lot farther, but that’s when everything went South. When that happens, you can’t do much about it. I was a young kid and impatient, looking for something to do, so I went to work for Brad Dorfman for a short period of time.

Photo: Grant Brittain

What year was that?

I started Acme in 1991, so I worked for Brad for about five or six months, from mid-1990 to the end of that year. I started shipping Acme stuff in March 1991. The idea for doing Acme skateboards happened while I worked for Brad. I presented it to Brad that I had an idea of a different style company. He didn’t really listen or care. To be honest, it was kind of funny how it ended with Brad. Then I took a loan on a house for $50,000, flipped it, and turned it into $150,000 the first day, which funded Acme.

Let’s talk about when we moved the Coke machine with Lester Kasai.

It was at the Hyatt in Long Beach. We decided we wanted to put the Coke machine in the elevator and just send it up and down just to freak people out. We also put couches in the elevator. We sat in the couches and went up and down. The door would open and we’d be sitting on the couch. We also broke the beds in the room by bouncing from bed to bed. We had adjoining rooms with a little conference room in-between. In the side room, we were doing flips off the beds, and I remember one of the bed frames collapsing. This all happened in one crazy night.

We unplugged the Coke machine that was in the little vending machine and ice area on the eighth or ninth floor. I don’t know how Lester ending up getting involved. He was the poor sucker who got on the other side of the Coke machine as we pushed it out. As we were getting ready to push the machine into the elevator, Lester was literally stuck behind it in the doorway. All of a sudden, we heard the elevator about to open and thought it was security, so we abandoned ship, but Lester was stuck behind the machine in the doorway. He could never push it out all by himself. All I could see was those little Asian eyes, pleading, “Jim, don’t leave me here.” I’ll never forget it. We scattered down the hallway, but, luckily, it wasn’t security. But, oh my God, the look in his eyes (laughs)! Unfortunately, the hotel was a little bit harder on the ASR crew next year. Sorry to the 8,000 people who attended ASR. We were the ones who caused that one.

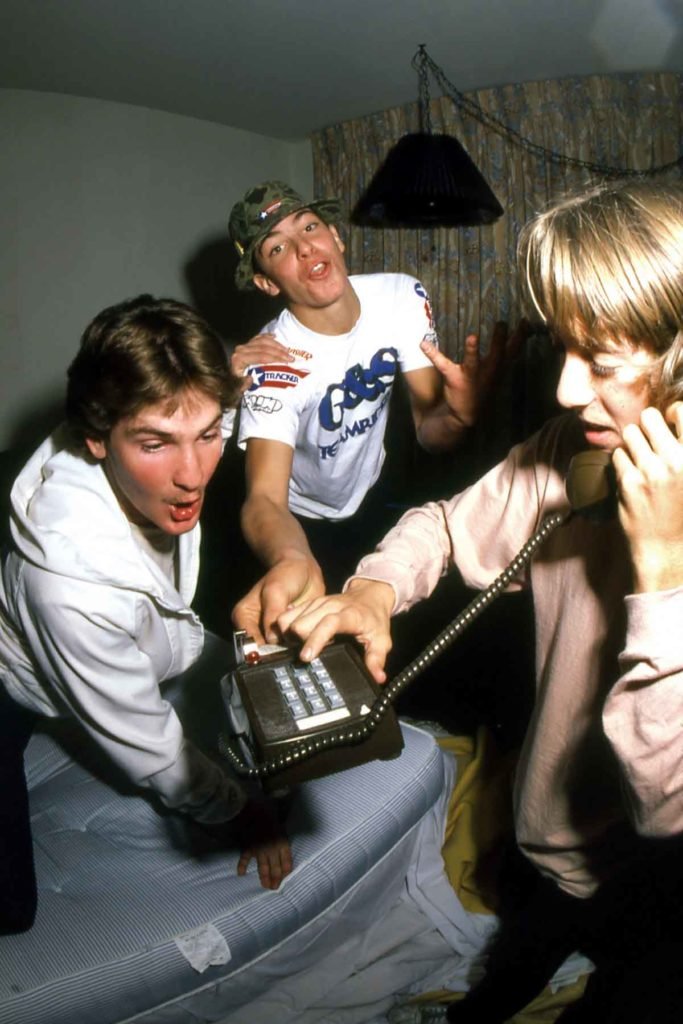

G&S team, Jim Gray, Neil Blender, and Billy Ruff, circa 1978.

Any closing thoughts on Tracker?

My roots on Tracker were honorable. I tried Trackers and Indys and decided I liked Trackers better. I’m not one who caves into peer pressure. Later, I started my own skateboard company and went completely against the grain, because I believed in something different. Some of our philosophies are the same. I’m not going to cower to friggin’ piss ants who try to talk shit. To this day, I’ll post a picture and some Indy guy will talk some shit. Dude, I will out fucking grind you and I will drill you into the hole if you fucking talk shit. If you can’t ride your trucks better than me, then don’t fucking talk about your trucks. I don’t’ care if you have an Indy tattoo on your balls. That doesn’t make you cool. I know more kooks with Indy tattoos than I do with Tracker tattoos, so who’s a bigger kook? The bottom line is they’re just skateboard trucks. You make a choice. I think Trackers are well-built, and I don’t like the way Indys turn. But, on the same point, Trackers turn differently. I know that, but they turn better for me. Trackers have a more proper steering, but they’re slower. Indy’s flop quicker, but flop constantly. When I made my Standard Trucks later in the ’90s, they were kind of somewhere in between.

I remember Buddy Carr gave me a set of Tracker Darts after I had been riding Standard Trucks for years. The Darts were just sitting there in a box, and I needed to put together a new board, but I was hesitant because I thought they were going to turn slow. I wasn’t really aware of the changes that had been made to them. I remember putting them together, going out in the parking lot, and thinking, “Oh, fuck! These things fucking turn completely, with a quicker response than they had.” So, I’ve been riding Trackers again. It has nothing to do with being on the team, it’s because I like them again. They rode good, and that was probably eight years ago, and I’ve just been riding them. They do work good. I’m one of the loose truck-riding older guys now. I’m riding pools with Steve Olson and all of those guys, and they don’t ride looser trucks than me anymore. I ride really loose trucks. I feel that, in a lot of ways, I’m a better skateboarder today at 50 than I was at 25—as far as board control, speed and confidence. People will see me carve on my board and think, “You can’t be riding Trackers.” And I’ll say, “Yeah, they’re Trackers. I’ll out carve you, out zigzag you.” I was impressed the Tracker Dart actually changed the game for me again. I don’t know if I could ride the same original Sixtracks today for the way I skate now because I do like my trucks looser. But, I like stability, I don’t like squirrely. The Dart is stable.

The difference is the roll center, the Dart turns more, but the Indy flops.

The Indy flops, it always has. You can see the way the Indy pivot cushions wear side to side because they drop left and drop right really quickly. But, I never liked the way they squirreled. I never had a squirrely feeling with Trackers. I know people buy Indys because lots of cool people ride them. Well, lots of cool people ride whatever other cool people get for free. Ride what fucking works, not what people get for free. Ride what someone would buy. What would you buy if you had to pay for it? That’s probably the truest thing you could find out about a product: what would pro athletes buy if they had to put their own money on the table for it?

Everyone knows if you ride Indy, Thunder, or Venture, you’re going to get coverage in Thrasher. It was in some ways painful to know you weren’t going to get coverage in Thrasher if you rode Tracker, and you probably weren’t going to get coverage in TransWorld either, because they so desperately didn’t want to be like Thrasher. It was kind of a double-whammy. It was like, you get hit from Nor Cal and you get hit from So Cal. What the fuck? I would rather be part of something honorable than the fucking cowards who did everything by shit-talking and backstabbing people. I have honor, but I’m not as cool, so call me an honorable uncool guy, rather than a super cool shit-talking backstabber.

Carving smooth in Malibu circa 2012